The best pitches aren’t about your idea

I.

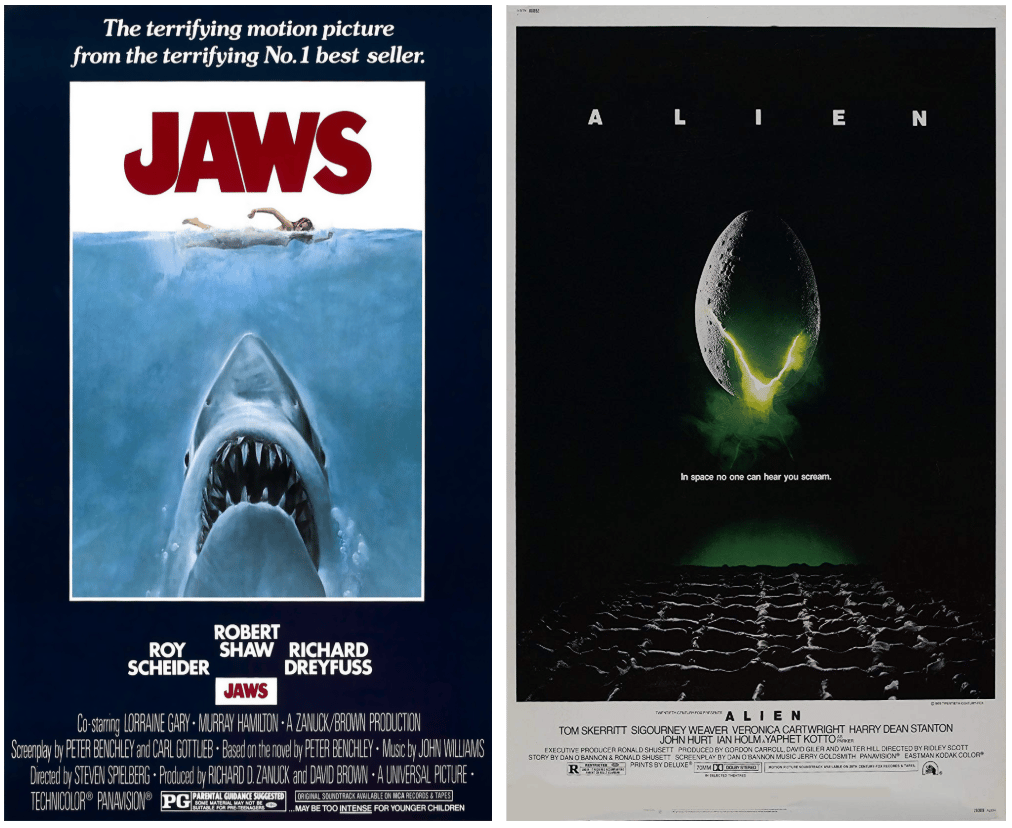

Dan O’Bannon and Ronald Shusett wrote Alien in desperation. O’Bannon was couchsurfing at Shusett’s place. He’d been working on a big-budget sci-fi film (Alejandro Jodorowsky’s doomed attempt at Dune) in Paris. When that project collapsed, he came back to Los Angeles. Broke. No apartment. No prospects. He crashed on his friend Ronald’s couch and decided to write a spec script that would actually sell.

When they walked into studios to pitch it, the development execs didn’t care enough about either of them to hear out elaborate presentations or careful world-building. So the pair figured out how to pitch the movie in three words:

“Jaws…in space.”

What blows me away about this pitch is its economy. In three monosyllabic words, O’Bannon and Shusett launched their concept into the same orbit as Jaws. Jaws had accomplished three huge achievements: it made shedloads of money, earned critical acclaim, and made a star out of the lead actor. Their simple phrase promised that their movie would do the same.

The pitch worked. Multiple studios wanted it. Fox won the bidding war. They picked Ridley Scott to direct it and the film became a phenomenon.

II.

The success of the first Alien movie rocketed Ridley Scott into the upper echelon of Hollywood directors. A sequel was inevitable, but at this point Ridley wasn’t interested. He’d said everything he was trying to say, and the studios didn’t want to pay him his new rate now that he was a bigshot.

Enter James Cameron. This is pre‑Titanic James Cameron, which means he’s hungry for his breakout opportunity. He manages to get a lunch with two producers. Immediately, the meeting starts on the back foot: “This is a no-win for you. If your movie’s good, Ridley will get the credit. If it’s bad, it’s all you. It’s a career ender,” one producer says.

Cameron can’t shake his excitement for Alien. But he’s got to recover this meeting. He flips his script over to the blank side of the page and writes one word in big block letters:

ALIEN

The executives nod.

He adds an S.

ALIEN

More nods.

He draws two vertical lines through the S, turning it into a dollar sign.

ALIEN$

The executives lean forward, nodding vigorously, their eyes lighting up.

Cameron got the job.

The audacity. I love how insane this story is. The confidence to throw a hail mary, putting on a mini-performance, a heat-seeking missile targeting the reward centers of the studio exec brain. It’s a bonus that the move was an embodiment of the two types of expertise Cameron claimed: a visual storyteller who can persuade an audience.

(This story is so ridiculous, it sounds like it can’t be true. So I looked it up. Cameron has confirmed it.)

III.

Two pitches. Two sets of creators. Two completely different approaches. But look closer and you’ll see they’re doing the same thing.

O’Bannon and Shusett knew studio executives didn’t want to be educated.. They wanted to be reassured. So the pitch didn’t explain Alien; it positioned it next to a proven winner. Three words that said: “You’ve already seen this work.”

Cameron knew his producers didn’t care about his artistic vision. They cared about ROI. So he didn’t talk about story or character. He drew a dollar sign. He showed them, in real time, that he understood exactly what they valued.

Both pitches succeeded because the creators stopped thinking about what they wanted to say and started thinking about what their audience needed to hear.

That’s the real lesson. Your pitch isn’t about your idea. It’s about understanding the person across the table so completely that you can give them exactly what they need to say yes. What keeps them up at night? What does success look like in their world? What language do they speak when no one’s watching?

Answer those questions, and you’re not even pitching anymore. You’re just offering them exactly what they’ve been looking for.

Does your pitch do that? Get that right, and the rest takes care of itself.

Thanks to readers of early drafts: Matthew Beebe, Rik Van Den Berge